Argentina’s

economic collapse is a valuable case-study because of its unique

circumstances. There are countries that have existed in poverty for

thousands of years, where most of the population has lived in awful

conditions their entire lives. While that is tragic, it does not

represent a good example as of what happens to a developed nation, both

economically and socially, when it collapses due to numerous factors

both local and foreign. When the world shuddered during the 1929

financial crisis, Argentina had the world’s 4th largest GDP. The country

had a strong and well-educated middle class, respectable local

industry, an enviable amount of natural resources and agriculture which

earned it the nickname of “granary of the world”.

I have often

written about how life after an economic collapse is not what most

people believe it to be. There’s no fancy bugging out into the woods,

there’s, zero, zip , nada use of most of the equipment that is so often

advertised as essential to survival. There’s no camping, no hunting, and

no epic battles against zombies or colorful Mad Max type gangs.

But

then again, what IS it like? What Discovery Channel and other reality

TV show “experts” tell us is not it. But what’s it like to live,

struggle, work and raise a family? What do you see happening during an

ordinary day? What concerns people? What works, and what doesn’t? The

short answer is in this article’s title. It’s the same, only worse.

Nothing good come out of it. Sure, you can say that surviving a plane

crash brought your family together, or getting over a disease made you

appreciate life more, but at the end of the day you don’t wish either

one on anyone.

Crime

Crime has always been a problem in Argentina but you could most

certainly see a drastic change after 2001. It used to be that everyone

locked their doors at night but some people had alarms in their houses,

some had fences and in even fewer cases some houses had burglar bars on

the windows. After 2001, you quickly saw home security becoming more of a

concern each passing month. A couple years later it was hard to spot a

house without burglar bars on the windows. Those that didn’t upscale

their home security ended up paying for it. On the streets it was the

same thing. Before 2001 everyone knew of someone that had been mugged,

maybe someone that had been carjacked or even an incident of home

invasion in the neighborhood once a year or so. By 2014 home invasions

are practically a daily occurrence in each neighborhood and it’s almost

impossible to find a person that hasn’t been a victim of crime in the

past decade. At the very least, people had a cellphone or a purse

snatch. It’s common to come across people that have been held at

gunpoint and carjacked not just once, but two times or more in recent

years. Every person I know has had a family member killed or at least

seriously wounded during a robbery. By 2011, Argentina was the country

with the most robberies in Latin America (UN data), with 973,3 robberies

per 100.000 inhabitants. Mexico came second with 688 robberies. Brazil

ended up in third place with 572,7.

http://www.infobae.com/2013/11/14/1523693-para-la-onu-argentina-es-el-pais-america-latina-mas-robos-habitante

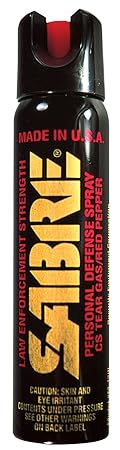

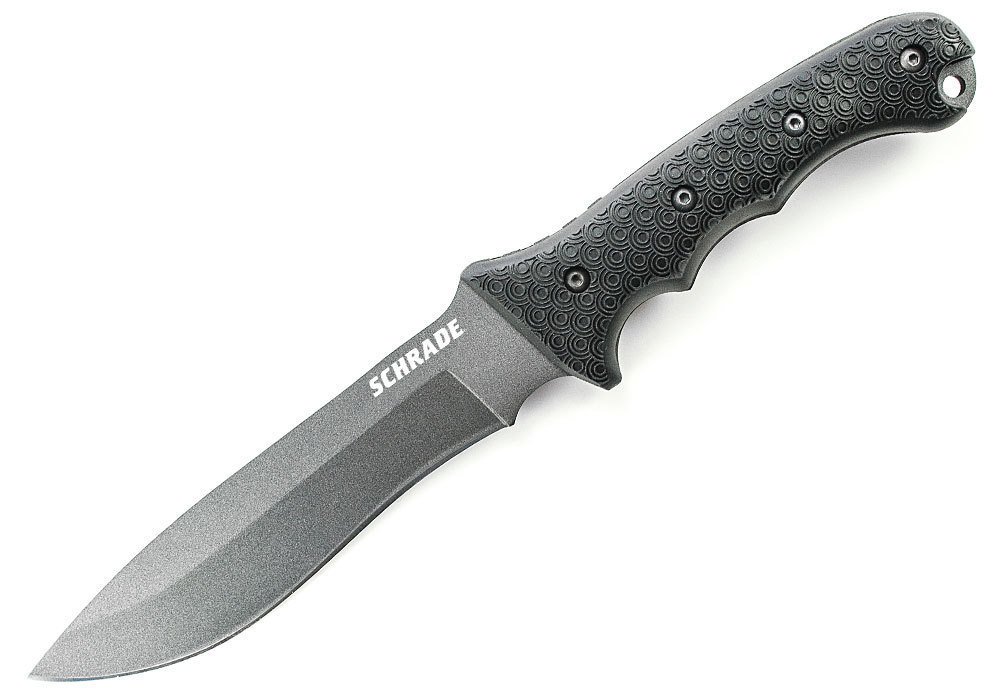

It becomes a part of life, you just deal with it and accept, yes,

that’s the word, you “accept” this as an inevitable part of life as much

as you accept the possibility of getting sick or being involved in a

car accident. When crime happens so often and it becomes such a high

risk factor you have two choices: You either accept it as a part of life

and chose not to worry beyond some basic common sense safety measures

and carry on with your life, trying not to worry about it anymore than

you worry about getting hit by lighting, or you do something about it.

You try to improve security in all aspects of life as much as possible,

home security, armed and unarmed self-defense, learning defensive

driving techniques, taking as many passive and active security measures

and precautions as you can. You carry weapons to defend yourself. You

learn how to use them. You make yourself as unappealing as a potential

victim as possible. You avoid dangerous situations and places. Basically

you learn to live in a constant state of alert. While the second path

is more likely to keep you safe, it’s also the more stressful one. I

don’t need to tell you which path most people end up taking.

Social Instability

As soon as banks close their doors, the protest started on the streets.

First in was against banks stealing people’s money. Then it was against

the politicians that allowed it. During the riots of December 19th and

20th of 2001 cars and buildings were burned down and over 30 people died

in various incidents across the country, but once the dust had settled

we understood that the rioting and civil unrest that we simply never saw

before to any considerable extent was now here to stay. Riots,

roadblocks and protests were part of everyday life. Sometimes they were

violent, sometimes stores got vandalized. The inflation, unemployment

and in many cases true hunger didn’t help. At times it was just a matter

of a grocery store giving up some food to avoid being looted.

Sometimes, when it was really just about a few hundred people showing up

half begging half demanding food, sometimes that was enough to avoid

getting a store looted. Most of all it was a matter of waking up every

day, checking the news to see if there was any ongoing protest or any

planned area of conflict and find alternative routes to wherever you

needed to go. If you got caught my a mob it could turn ugly, but in

general it was more of a nuisance, knowing you would waste a couple

hours of your day just to cover a few miles across the city. Strikes

also occurred with frequency, sometimes unannounced. You’d lose buses,

trains, even flights because of this or that group going on strike. If

you had a child in a public school, you could expect him to lose up to

30% of class days due to one form of strike or union problem or another.

Public offices were particularly prone to this type of problem. Between

strikes, those days when the network went down, or there was no power,

combined with their natural incompetence made any paperwork involving

public workers a true nightmare. You need to have your car’s annual

check or test? No problem. Be ready to lose your entire day for

something that shouldn’t take more than 20 minutes in any half civilized

country.

This would become a common pattern in Argentina. Thing’s

“sort of” work. You have cops in Argentina, but you better know how to

defend yourself. You have an electric grid and you pay your power bill,

but expect to go 2 or 3 days a week without power in summer. You have

tap water, you sure pay for it, but only a fool would drink it without

filtering first.

Power

Electric power is one of the best metaphors of the situation in

Argentina: It doesn’t work when you need it the most, and even when it

does it’s of awful quality. When you do have electricity, it’s usually

of lower voltage than the standard 220V. Sometimes it’s so low air

conditioners and microwaves won’t even work, and that’s when you have

power. During summer time when electricity is in greater demand because

of the intense South American heat, expect frequent outages which may

last days, even weeks in some cases. The reasons for these problems are

numerous. Because of poor regulations and corruption companies rarely

kept up with the necessary infrastructure updates. This only got worse

after 2001 with the devaluation and price increase of imported supplies.

Power has been subsidized in Argentina for several years now and the

price has been kept down artificially, making the problem of lack of

investment even worse. During summer time it’s common for transformers

to blow up. There’s also the constant problem of cable theft due to

their copper content. Because of the lack of investment in power

generation, along with thousands of millions spend in projects where the

money disappeared without a single brick ever being laid, Argentina was

forced to spend 9.500 million Usd importing energy in 2011 alone.

If you expect to have power, you better get yourself a generator.

Without one most stores wouldn’t be able to stay open for business. A

voltage elevator is also a necessary investment so as to compensate for

the low voltage “dirty” power that at times is useless.

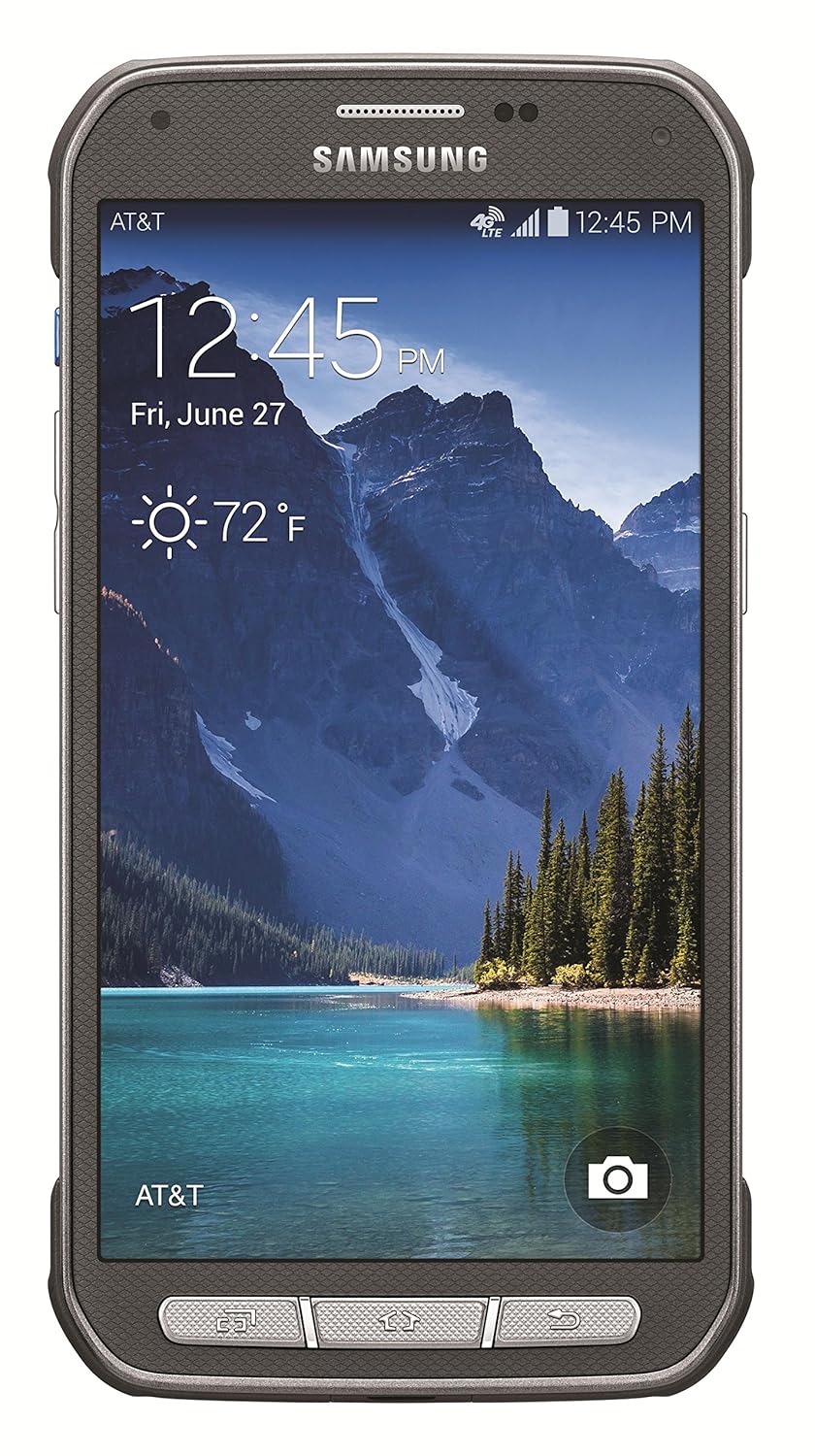

Communications

Something similar happens regarding telecommunications. The lack of

investment while adding new customers means the network is

oversaturated. Operators in Argentina work at 135 MHz, which is half or

what they use in Chile and one third of what’s used in Brazil. It is

estimated that over 60% of the calls experience problems, from lack of

signal to dropped calls. Cell phone communication falls, again, in that

gray area of post-2001 Argentina: they kinda work, sometimes. You can

pay for 3G connection, but getting it is a matter of luck.

Floods

The problem is again, lack of investment and infrastructure. It also

comes into play the enormous amount of litter on the streets which clog

storm drains. Storm drains are also made of pretty heavy metal so…

remember the inflation problems, along with crime and unemployment?

Storm drain grated inlets are usually made of heavy iron. That iron

fetches a nice price when sold, so these where stolen all over the

country. Everything from statues, historic plaques in monuments and even

doorknobs have been stolen because of the price of metals.

If flood

prevention investment is a problem in developed nations, you can

imagine how bad it gets in a place like Argentina. Without hurricanes or

even serious storms, just heavy rain is enough to end in tragedy. In

April 2013 a flood in the capital city La Plata claimed over 100 lives.

As years go by and the infrastructure is not only not upgraded but

deteriorating, floods are yet another problem people in Buenos Aires

have to deal with.

Transportation

Driving around Buenos Aires isn’t for everyone. Roads are in awful

condition, people literally drive like maniacs and if that’s not enough,

you also have to worry about getting carjacked or mugged in a red

light. People from developed nations that try to drive in Argentina

usually give up after the first attempt. They can’t understand why no

one respects basic traffic rules, why they seem to cut you off for no

reason, let alone roll down the window and insult you.

Yet again,

lack of investment and corruption is key to explain why this happens.

The money that is stolen isnt there to put up traffic signs, fix roads

or build more of them. There’s no investment in driver education either.

More often than not people get their license by bribing someone rather

than actually doing the test. In my case, it took me all day to get my

driver’s license simply because I refused to pay a bit extra to get it

right away. In each stage, the sight test, theory test, practical test,

in each one I had to explain that no, I don’t want to “pay” to get it

quicker. I must have been the only guy that day that went through the

entire process. With uneducated drivers you can imagine what kind of

people are behind the wheel. Add to that the overall poverty level and

poor condition of the cars on the streets, and combine it with the level

of stress and violence the entire population is subjected to.

In

the case of public transportation it is again, far from ideal. Train

accidents with fatalities keep happening for the same reasons:

Corruption, lack of control, lack of investment and politics getting in

the way of doing things right. Traveling in train, subway or bus during

rush hour lets you experience what a sardine feels like when it’s

getting canned. The service is overall unreliable. Busses and trains

break down often. There’s also strikes and remember those protests and

road blocks to complicate things further.

FerFAL

Fernando “FerFAL” Aguirre is the author of “The Modern Survival Manual: Surviving the Economic Collapse” and “Bugging Out and Relocating: When Staying is not an Option”.

Fenix PD20

Single CR123 cell. 6 modes including 180 lumen turbo mode.

General Mode: 9 lumens (35hrs) -> 47 lumens (6.5hrs) -> 94 lumens (2.6hrs) -> SOS

Turbo Mode: 180 lumens (1hrs) -> Strobe

15 days of survival use (2 continuous hours per day on the lowest setting)

Fenix PD20

Single CR123 cell. 6 modes including 180 lumen turbo mode.

General Mode: 9 lumens (35hrs) -> 47 lumens (6.5hrs) -> 94 lumens (2.6hrs) -> SOS

Turbo Mode: 180 lumens (1hrs) -> Strobe

15 days of survival use (2 continuous hours per day on the lowest setting)